The current slump in bus and train usage due to covid-19 raises the question of how public transport can recover once continuing medical advances diminish the coronavirus health risks. Transport Scotland figures show rail use at only 30% of previous levels, with 60% of bus users having returned.

More home working and online shopping are expected to continue. Lower fare income means many bus services are now loss-making and the ScotRail subsidy has risen. Train services have been cut, particularly on Central Belt commuter routes.

But around 30% of households have no car and depend on public transport. In future, as the economy recovers, overcoming road congestion, pollution, CO2 emissions and rising electrical power consumption will depend on attracting more people to switch from car to active travel and public transport. A recovery strategy for public transport is needed. Fundamental change may be necessary.

Transport Integration

Transport integration is a strategy that should be considered. In continental countries where bus and rail services are co-ordinated, buses and trains connect at transport interchanges making through journeys easier. In these countries, bus use has consistently grown over the years. For instance, Swiss Postbus passenger numbers grew by 18% over five years to 2019, while Scottish bus use fell by 10%.

Bus and rail co-ordination on the continent is planned by local transport and rail authorities. In Scotland, the Transport (Scotland) Act 2019 made provision for bus franchising or direct control of buses by local authorities. ScotRail services are now directly specified by Transport Scotland. This is an opportunity to consider an integrated public transport framework for Scotland. Bus services and railway timetables could be restructured to create a comprehensive transport network. This would meet one objective of the Scottish Government’s National Transport Strategy (2016) to “improve integration by making journey planning and ticketing easier, and working to ensure smooth connection between different forms of transport”.

Affordability is a prime consideration, particularly as bus and train revenue is now lower. Progressing from bus competition to franchising and bus/rail integration would mean routes could be rationalised to reduce duplication and costs. Public funding for buses could be consolidated into a new Bus Integration Grant allocated through local transport authorities to fund bus franchises (see Section 3). Train services could be optimised to attract users back to rail and improve viability (see Section 4).

In Scotland’s biggest cities, integrated transport networks could transform travel and reduce city centre road traffic. Edinburgh City Council is already planning to integrate Lothian Buses with Edinburgh Trams to improve connections and reduce bus traffic on Princes Street. Bus franchising or municipal ownership in Glasgow would enable bus routes to co-ordinate with the modernised Subway and suburban rail network, allowing more street space to be allocated to walking and cycling.

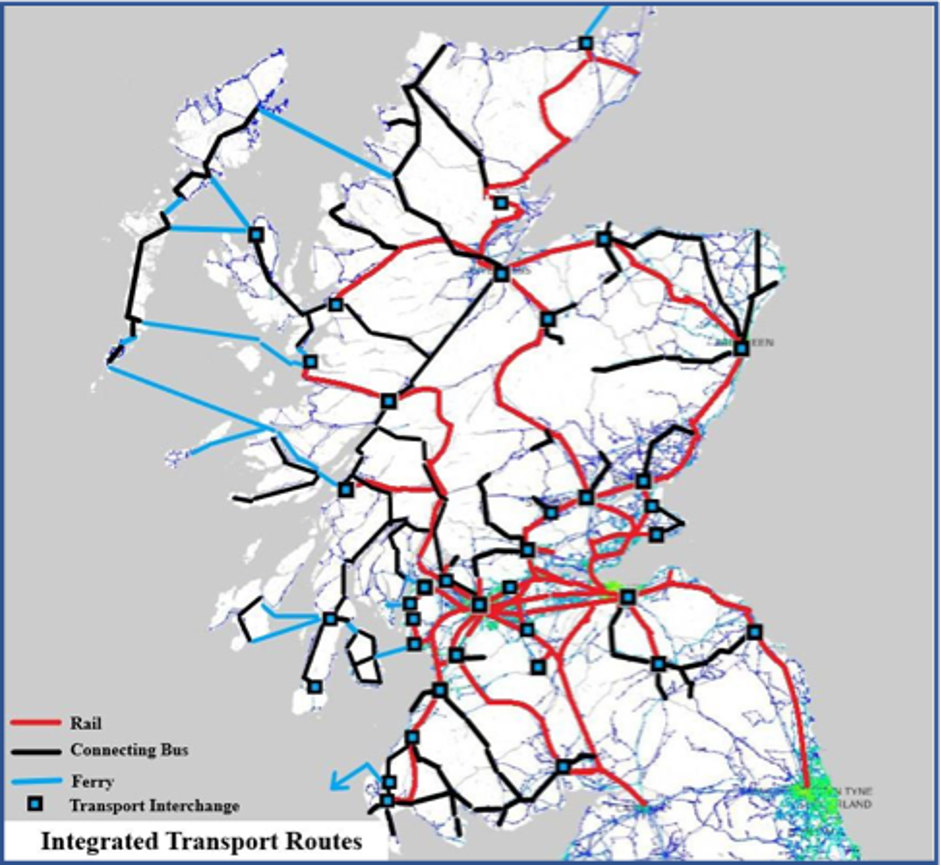

Co-ordinated bus and rail services connecting at regional transport interchanges would make it easier for local people and tourists to use public transport in rural areas. The need for people to take their cars on ferries (costly environmentally and financially) could be reduced by improving public transport connections, both on islands and the mainland, with ferry saiings. The map on page 4 shows how an integrated public transport network would improve connectivity across the country.

Covid-19 and the climate change crisis are making public transport improvements more urgent. The next sections outline how bus and rail planners could respond to these challenges.

Co-ordinated Bus Franchises

Missing the Bus

Most local bus services in Scotland operated commercially pre-covid, catering for local needs including school travel. There are often no connections with trains or other bus routes. Even on subsidised routes, many timetables are not planned with connectivity in mind.

Lack of connections was raised as a major hindrance to bus use in the South West Scotland Transport Study (January 2020). As an example from this area, it is worth analysing Stagecoach Route 359 between Newton Stewart and Girvan. The first bus from Girvan to Newton Stewart leaves Girvan station at 08.51. The train from Glasgow and Ayr arrives at 08.55, missing the bus by four minutes! Northbound, the last bus from Newton Stewart arrives at Girvan station at 17.01, two minutes after the train for Ayr and Glasgow has left at 16.59! The rest of the day connections are no better, so journeys by public transport from Glasgow to Newton Stewart average 3 hours 40 minutes, almost twice the two-hour car journey time. Minor timetable adjustments to connect at Girvan with trains to Ayr and Glasgow would cut public transport journey times from Glasgow by almost an hour to 2 hours 45 minutes.

Swiss Integration Success

Many European countries have developed national travel systems making it easy for people to go by train and bus between any places. Rail provides the backbone network. Interchange hubs between train and local bus, underground or tram allow people to travel seamlessly between any points on the local and wider area network. Reliable connections and a unified ticketing system are important. In countries with integrated public transport, bus use has been rising in contrast with decline in Scotland, as can be seen by comparing Swiss Postbus and Scottish local bus use over 5 years:

| SwissPost | Scotland | |

| 2014 | 141M | 421M |

| 2019 | 167M | 380M |

| +18% | -10% |

Integrating Scottish Transport

With the financial position of buses and trains undermined by Covid-19, maintaining existing level of bus and rail services would need greatly increased public funding. Without this, public transport as currently organised will decline, leaving many bus routes vulnerable.

It’s time for a bold new approach. A high-level objective of the Scottish Government’s National Transport Strategy (2016) is improved integration of public transport. A new bus franchising system should be implemented to achieve this, replacing the existing competitive, un-coordinated (and now largely unviable) bus framework. The franchise agreements could incorporate government-backed capital investment in bus priority measures and new green bus fleets as a major relaunch of bus travel. The full package could include:

- Bus franchising system let by local authorities/RTPs. Franchise specification would cover local travel needs including school travel, and also connections with other bus routes and the rail network where possible. Routes would be rationalised to reduce duplication and integrate with rail, tram and subway.

- Bus Integration Grant, consolidating the current BSOG, concession scheme, and local authority bus subsidies (£314M in 2018/19), to support the co-ordinated bus services specified in the franchises.

- Green Bus Fleet with new low-emission buses acquired on a leasing basis by transport authorities to be used by franchisees for the duration of the franchise. This would boost the bus construction industry.

- Bus priority infrastructure investment as announced in the £500M scheme by the Scottish Government in 2019. This would include traffic management schemes and development of bus/rail interchanges.

Roles and Responsibilities

The strategy outlined above for bus franchising will give a greater role for local authorities/RTPs in planning services to be included in franchises, in consultation with bus operators.

The Bus Integration Grant funding model proposed in this note would be controlled by Transport Scotland’s Bus, Accessibility & Active Travel Directorate, co-operating with local authorities/RTPs who would oversee the individual franchise agreements.

Public Transport Integration needs co-ordination of bus and rail routes and timetables. Transport Scotland’s Rail Directorate when specifying future ScotRail services will need to work with the TS Bus Directorate and local authority/RTPS to ensure that trains and franchised buses connect reliably at interchanges, and that fares and ticketing permit seamless multi-modal journeys.

Rail Review

Phasing out sales of petrol and diesel cars by 2032 will cut road carbon emissions but the electricity generation and distribution network does not have capacity to power the current level of road traffic. With nuclear and hydrocarbon electricity generation dwindling and finite renewables development, an energy crisis will occur unless active travel and public transport play much greater roles.

Action to rebuild rail use when Covid-19 subsides should be the cornerstone of the Scottish Government zero net carbon programme in response to the climate change threat. Four objectives should be met:

- Long distance inter-urban travel by rail needs to be faster than by car

- Central Belt urban rail services need to recover towards pre-pandemic “turn up and go” frequencies

- Scenic routes should be developed as unique assets to boost Scotland’s ailing tourist industry

- Bus interchange facilities are needed at interchange stations

InterCity

To recover and expand rail’s market share for long distance travel, journeys by train need to be quicker than by car. The ScotRail Inter7City High Speed Trains are faster than the previous Turbostar trains. Transport Scotland’s welcome InterCity Electrification proposed in the Rail Decarbonisation Plan should shave more minutes off long distance journeys. Journey times could be shortened further by:

- Investment to remodel junctions to increase speeds (eg at Perth and elsewhere)

- Replacement of some level crossings by bridges or underpasses where rail speed is restricted

- New loops on single track lines (eg at Ballinluig and on A2I line)

to allow faster more reliable schedules.

Train journeys with these improvements could be faster than by car, with best rail journey targets below:

| Glasgow-Perth | 50 minutes | Edinburgh-Perth | 1 hour |

| Glasgow-Dundee | 1 hour 10 minutes | Edinburgh-Dundee | 1 hour |

| Glasgow-Aberdeen | 2 hours 10 minutes | Edinburgh-Aberdeen | 2 hours |

| Glasgow-Inverness | 2 hours 40 minutes | Edinburgh-Inverness | 2 hours 50 minutes |

| Aberdeen-Inverness | 2 hours |

Urban Routes

With rail use currently running at 30% of pre-pandemic level, service frequencies cut, and home working expected to continue for many people, rail commuter revenue will stay below budget for some time. But more reliance on cars increases road congestion, accidents, pollution and CO2 emissions.

On many routes in the Central Belt, formerly with 15-minute services but now reduced to half-hourly off- peak, upgrading to a 20-minute service would restore most of the customer benefits (with a 10-minute average wait between trains, rather than the former 7.5 minutes), but would reduce train miles and running costs by 25% compared with the pre-pandemic service. Adopting a 20-minute pattern on some routes would involve major re-timetabling but an initial check suggests this might be feasible. The West Coast Main Line from London Euston is based on 20-minute interval services. Further work by Transport Scotland and Network Rail would confirm whether this could form the basis of more cost-effective Central Belt timetables.

Scenic Routes

The Scottish tourist industry has been badly hit by the pandemic. The lines to Mallaig, Oban, Kyle, Stranraer and the Far North are world class scenic routes that, with more marketing, can play a greater part in boosting visitor numbers. New trains envisaged in the Rail Decarbonisation Plan should be designed to give visitors an enhanced “green” travel experience through the Scottish countryside.

Bus/Rail Interchanges

Transport integration as advocated in this paper would increase footfall through transport interchanges. The integrated route map (page 4) shows some proposed transport interchanges across the country. Station approach roads and access to platforms would in many cases need upgrades to make the transfer between train and bus as convenient as possible.

Public Transport Relaunch for COP26

The map above shows how an integrated bus and rail route network would improve nationwide connectivity. Towns across the country from Newton Stewart and Selkirk in the south to Lossiemouth and Grantown in the north would be readily accessible by bus links from transport interchanges like Girvan, Galashiels, Elgin and Aviemore on the national rail network. A unified smart fares system would simplify ticketing on multi-modal journeys.

Integrated urban transport networks would make many journeys within cities easier and cheaper by public transport. In Edinburgh and Glasgow, rationalising public transport routes could make more use of interchanges with trains, trams and subway to cut bus operating costs and city centre road traffic.

The image and viability of public transport has been badly affected by the pandemic. The transport integration framework outlined in this paper is an opportunity for the Scottish Government to relaunch ScotRail and co-ordinated bus services as a green transport initiative in time for the COP26 world summit in Glasgow in November 2021.